Two men sit across a table. One is just there to listen. The other, an 80-something who never got around to retirement, speaks in a halting voice of his memories and the possessions that keep them straight. He wanders aloud through his son’s death; his attendance at funerals in since-dissolved countries; his hopes across his long, long career, and the pinnacle of that career, his assurance that history will forgive him. Through splintered memories the old man discusses his parents, his education, his aspirations fulfilled and unfulfilled, and so much that cannot be pieced back together. No one asked him about these topics; they simply emerge.

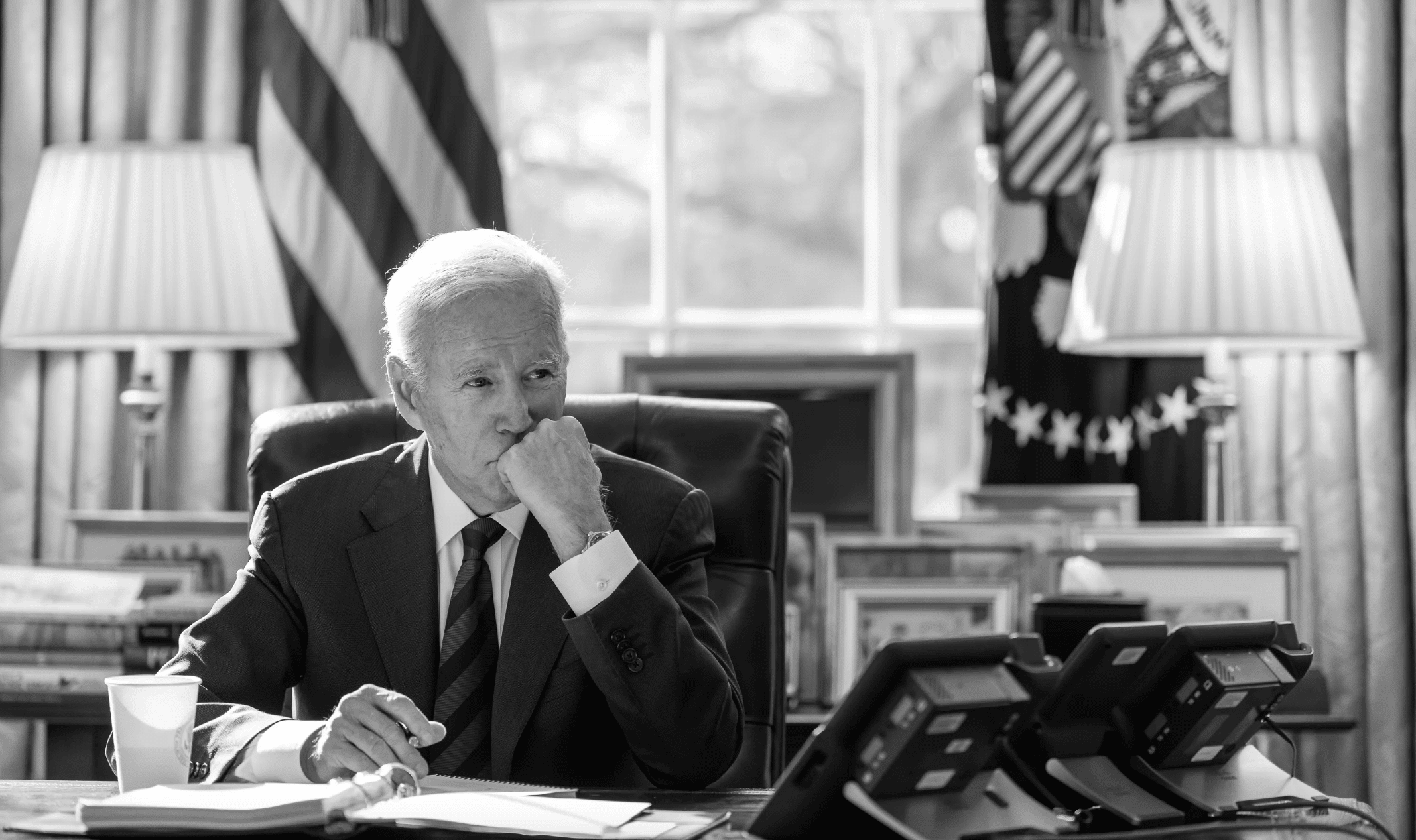

It’s a scene fit for the stage. Joe Biden’s five-hour interview with special counsel Robert Hur, told piecemeal in the latter’s almost 400-page report, transcends its intended genre. And while it had its moment in the news earlier this spring, this tragicomic character study of America’s oldest president risks being buried under far less interesting stories. The news coverage of the report never quite captured it, but all the irony and futility of Biden’s long political career converged in this conversation and its aftermath, as if Willy Loman himself were stalking the halls of the White House.

Headlines about the report wrote themselves as soon as the special counsel’s office released it. Immediate reactions focused on a single sentence on page six: “Biden would likely present himself to a jury, as he did during our interview of him, as a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.” The congressional hearing that followed zeroed in on this line. Republicans focused on the last two words—and the numerous examples throughout the report of Biden’s memory failing him. Democrats dismissed the line as Hur taking unnecessary cheap shots at the president but otherwise tried to focus the public on the special counsel’s decision not to prosecute—move along, nothing to see here.

Technically speaking, neither portrayal of Hur’s rationale was quite correct. There is, in fact, something to see here; Biden clearly mishandled documents containing confidential (including top secret) information, and even shared them with someone who did not have security clearance. Hur does not absolve him of doing so, but neither does he pin that absolution primarily on Biden’s senility. Rather, it’s Biden’s overwhelming earnestness, and the fact that the relevant statutes all mention “intent,” that gets the president off the hook here. He can—and in court, almost certainly would—simply say he didn’t mean to do it, or that he sincerely thought he could do it, and that would be enough of a defense that it wouldn’t be worth the government’s time to bring a case.

But that isn’t what made the Hur report so poignant, so interesting—so funny. It’s something neither party nor much of the news coverage mentioned at all; the biggest missing detail from the stories elected officials told about the Hur report isn’t any legal technicality in the decision not to prosecute Biden for holding on to classified documents. It’s what Biden held on to, and why.

The centerpiece of the investigation is a lengthy memo Biden wrote in 2009 to then-president Barack Obama, which investigators found—along with classified materials used to draft it—tucked in a cardboard box in Biden’s garage in Delaware last year. It was an artifact from what Biden at one time believed (and perhaps, Hur surmised, still believes) to be the most important moment of his political career.

In fall 2009, less than a year into Obama’s presidency, the cabinet had to decide just how far it was willing to depart from its predecessor’s (by then) highly unpopular foreign policy. At issue was “the surge”: a request for 40,000 additional troops on the ground in Afghanistan. The defense establishment was, of course, in favor, assuring the president that where naked military force had failed, military force under the guise of “counterinsurgency/COIN” and “nation-building” would succeed. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was in favor, as were Defense Secretary Robert Gates, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Michael Mullen, and just about everyone else. The only person who dissented, who made it a discussion at all, the person everyone else rolled their eyes at and dismissed as a crank, was the vice president.

He was, by their standards, a doe-eyed peacenik; he still supported increasing troop levels, but only by half the number the Pentagon wanted. He called the military lobbying for the surge “f*cking outrageous.” He did all he could in meetings to “punch a hole in the logic” driving toward a surge. He wouldn’t shut up about Vietnam.

Thanksgiving approached, and Obama had to make a final decision. Biden knew this would be his last chance. “If I succeed in slowing down or stopping this misguided buildup it will make taking this job worthwhile. This decision will define our Admin in history,” he wrote in a notebook (which he holds onto to this day). “I don’t want history to associate me with the adoption of a COIN [strategy].” On vacation for Thanksgiving in Nantucket, Biden wrote two memos to Obama, one the day before the holiday with his staff and one by himself three days later. The latter was the only memo he ever wrote exclusively for the president. Biden’s 20-page memo, leaked in 2012 amid Obama’s reelection campaign, was desperate: “I do not see how anyone who took part in our discussions could emerge without profound questions about the viability of counterinsurgency,” Biden wrote. He reminded the president that “no one can tell you with conviction when, and even if, we can produce the flip sides of COIN,” i.e., a functional Afghan government and independent Afghan security forces.

Two days after receiving Biden’s last plea, Obama announced a compromise: there would be a surge, but troop numbers would split the difference between what Biden wanted and what the rest of the cabinet and joint chiefs wanted. And the new troops would follow a strategy of counterinsurgency, aimed at fostering “a civilian surge that reinforces positive action.” The president in his announcement issued a direct rebuke to “those who suggest that Afghanistan is another Vietnam”—that is, to Biden. He reaffirmed the case for war, dooming the country to another decade-plus of bloodshed.

Biden considered resigning. A second Vietnam had become inevitable. The president had surrounded himself with hawks and his “compromise” had given them almost everything they had asked for. But that echo chamber, Biden reasoned, was just as good a reason for him to stay. After all, how much further would the president go if not a single person in the room voiced any hesitation about a military operation? In public, Biden moved on from the surge debate, but—consciously or not—held onto the Thanksgiving memo and the documents he used to draft it. Those papers, almost 15 years later, would be stored in a beat-up box in a garage next to tax documents and pictures of Beau. Investigators were able to identify them as belonging to the now-president because they were in a folder labeled, in true Biden fashion, “AFGANASTAN.”

In his interview with the special counsel, Biden had two forms: short back-and-forth responses, usually to say he didn’t recall something; and long tangents. There was no telling which questions would send him in which of the two directions. The president gave one-sentence answers to query after query about who handled files, whose documents were in such and such filing cabinet, and so on. But then, out of the blue, the question “how often did you use this drawer” sent him on a 10-minute reverie ranging from his dream of attending architectural school to his longtime aspiration to donate a million dollars to charity to the time Colin Powell and Chuck Hagel recommended an accountant. His “answer” to the question “did you bring classified material with you from the West Wing or the Naval Observatory to the Lake House” also surpassed the 10-minute mark, and included such gems as “I just hope you didn’t find any risqué pictures of my wife in a bathing suit”; “How many people you know did—eulogize Teddy and Strom Thurmond?”; “I’m a frustrated architect”; and “I, unfortunately, embarrassed the hell out of the leader of Mongolia,” not to mention several stretches in the transcript marked “indiscernible.”

But likewise, Biden’s tangents seem to have two modes. Some are half remembered, anecdotal, and barely connected, if at all. Such are the asides about Mongolia and Colin Powell, or the lengthy meander through recollections of law school the president delivers in answer to the question of where he kept certain documents in the Naval Observatory. Other tangents, however, go down paths that are more deeply known, stories Biden has obviously told and retold to himself and others.

Biden told two such stories in the interview. The first, which the investigators did not ask for (and at one point tried, fruitlessly, to interrupt), is the story behind the title of his book Promise Me, Dad, in which his son Beau begs him to stay engaged in politics in the Era of Trump. This being the main subject of a book for which he did a lengthy tour and a tale he’d repeated in public speeches as recently as October, it’s no surprise Biden can tell it with a directness and clarity not afforded “the leader of Mongolia.”

The other story is that of the Thanksgiving memo. Deputy Special Counsel Marc Krickbaum asked him for this one. Biden’s personal counsel objected, asking if it was an “appropriate question,” but the president cut him off: “I’ll tell you why I wrote it…. I was trying to change the president’s mind, and I wanted to let him know I was ready to speak out no matter unless he told me don’t say a word, I’m ready to speak out, and to really, quite frankly, save his ass on what was going on.” The personal counsel interjected again to warn Hur that his client might not “feel comfortable describing confidential advice that he provided.” Hur responded that “well, the president seems eminently comfortable” telling the story.

And indeed he did, as far as the transcript can convey. The topic seems to send Biden right back to November 2009. This is no half-told anecdote or flubbed one-liner; this is a memory he’s clearly happy to dwell on and one he’s proud to think about. More than three hours into the interview, the clarity and focus of Biden’s recollection must have stood out to everyone at the table.

It obviously stood out to Hur. It seemed that the memo held some special place in the president’s understanding of himself, even if that place was not very clear, even to Biden. “Mr. Biden,” Hur writes in his final report, “has long seen himself as a historic figure.” He “collected papers and artifacts related to significant issues and events in his career” and used them to write memoirs “to document his legacy, and to cite as evidence that he was a man of presidential timber.” The Thanksgiving memo, in Hur’s telling, is Biden’s Rosebud—the sign of his innocence, held on to through the years, the token proving that he was worthy of the political office he spent so many years trying to reach. After a career full of decisions, personal and political alike, that would age so poorly—busing and sniffing hair and flattering segregationists and blatant plagiarism and supporting war in Iraq—Biden felt that at least this once, “history would prove him right.” So he kept the memo, as he told the special counsel, “for posterity’s sake.”

Biden’s legal team, of course, disputed Hur’s portrayal. The memo meant nothing to Biden, they say—it ended up in his garage by mistake. Democratic members of the House Judiciary Committee didn’t mention the memo at all in last month’s hearings, and Biden’s campaign surrogates have similarly ignored it in media appearances. Their sole response to the entire affair has been to ask the media and the public to focus instead on Donald Trump, with occasional accusations that Hur had been a secret MAGA operative all along.

This seems like obvious political malpractice. The campaign team should be embracing the opportunity to talk about the memo. The talking points write themselves: Biden had been right; Biden had seen the future; Biden should get credit for telling hard truths. They should be trotting out what Hur called the “evidence that he was a man of presidential timber.”

Yet all Biden’s camp can do with this unearthed monument of Biden’s legacy is to immediately bury it again. Why? One reason is that the people who were wrong about Afghanistan are either still too politically influential or are too sacrosanct to have their legacy tarnished by any clear statement of the war’s obvious failure. Or both, in the case of Barack Obama. Biden still sits in the shadow of his old boss, the man who had been wrong in 2009 and who told him in 2016 to step aside for Hillary Clinton (who, lest it be forgotten, had also been wrong in 2009). Obama remains too heroic in party memory and probably too powerful even today for a Democratic campaign to risk making him look bad. Not even Biden can bring himself to criticize his predecessor. One gets the sense, especially from the transcript of his interview with Hur, that Biden is still making himself think highly of Obama and telling himself Obama thought highly of him. Add it to the long list of ironies in Biden’s presidency: The person who brought him into the executive branch held him back in 2016, and is still holding him back.

Another reason could be the intense criticism Biden received over the August 2021 Afghanistan withdrawal. Perhaps his party is afraid of using “Biden” and “Afghanistan” in the same sentence ever again. But here too looms Obama’s shadow. A messy withdrawal became inevitable when Obama chose to keep the war going and stamped it as a bipartisan affair. Biden would be proven right in his 2009 assertion that, COIN or no COIN, Afghanistan’s government and security forces would be flimsy, but only in the process of himself taking the fall for it.

The one thing Biden got wrong in the surge debate was his prediction that “this decision will define our Admin in history.” He underestimated how willing his compatriots would be to memory-hole it, even now that they nominally work for him. The people and the party that gave Biden what he really wanted after a half century of dirty work are, it turns out, structurally committed to being wrong. They have to deny him his one chance at being remembered for something good for a change.

Biden is cursed to be the anti-Obama. Obama gets to enjoy a legacy, a spotless reputation among party functionaries—the same functionaries who now staff the Biden administration and run the campaign. Obama gets to be his own man, untainted by association with his direct successor, while the case for Biden is only ever about Trump. Biden gets the shame over Vietnam 2.0 that should, in no small part, be Obama’s.

Even to this day Biden holds out hope that he will get to be the important one, the one who saved democracy. He carries on in denial of the reality that the forces that brought him into power have already written his story. He is doomed; he can never assert his one moment of innocence over decades of bad decisions. All those decisions, but more likely his mental decline as president and potentially losing to Trump because he refused to let someone younger run, will almost certainly be Biden’s true legacy. But for one holiday weekend in the course of those decades, he was right, and he knew it. And he told the special counsel and wrote in his notebooks that he hoped history would remember it, and think well of him.

This drama has one final twist: Joe Biden told Robert Hur exactly why he kept the memo. Or tried, at least. His explanation is admittedly so odd and so misplaced that all present clearly assumed he had lost the thread of the conversation. In trying to get him back on track, the lawyers brought to a premature end the very story they were trying to get out of Biden.

Here is the president’s explanation for his actions:

I—I’ve been of the view, from a historical standpoint, that there are certain points in history, world history, where fundamental things change, usually technology. For example, without Gutenberg’s printing press, Europe would be a very different place. Literally a different place, because the country would not have known what was happening in other countries—other parts of the country. You know, think about a stupid idea, a notion. Nixon probably would have been President where he used the television where he’s sweating—I mean, sincerely. He was sweating so profusely in that debate, a lot of people thought he won the debate, but he lost the debate because of his demeanor. The—so there’s a lot of things that I think are fundamentally changing how international societies function. And they relate a lot to technology. And one of the things that I was of the view, that a lot has changed in terms of everything from the Internet to the way in which we communicate with one another, to—that has fundamentally altered the ability—I’ve had this discussion with the press—

And there Krickbaum cut him off. Hur included none of this soliloquy in his final report, even though Biden followed it up with “that’s why I wanted it, it had nothing to do with Afghanistan”—seemingly offering up a motive for the very crime the special counsel was investigating. And who can blame Hur for brushing past it? It makes so little sense. Only Biden himself could fully understand what these vague gestures toward Marshall McLuhan have to do with the Afghanistan memo. But it seems the president is saying that he kept the document as a token of its technological era. As if the most significant thing about it is that he sent it over fax, rather than email.

This is such an unbelievably, maddeningly mundane (and, let’s be honest, very stupid) reason to hold on to the document all these years. Thousands of lives, the fate of a country and a war and a presidency depended on how convincing this one memo could be, yet these stakes seem utterly lost on Biden. He can no longer claim his little victory even in the shelter of his own mind. If the memo ever signified his worthiness or prudence or the judgment of history, it does not now, not even to him.

Biden’s nonsensical explanation makes too much sense of his other remarks and attitudes. He wanted to keep the memo “for posterity’s sake,” yes, but as an apolitical time capsule. He “see[s] himself as a historic figure,” but only in the sense of happening to have been the warm body in office during a transitional time in world history. When the curtain closes, that will be the Biden legacy. Our protagonist will have learned only to forget, unearthed his heroic past only to bury it again.

Originally found on American Conservative. Read More