The Ohio River tears westward through the Pittsburgh suburbs, whisks into West Virginia, cuts on through Ohio, capstones Kentucky, indexes Indiana, and terminates in Southern Illinois. In the end, it marries the mighty Mississippi. The Ohio River once marked the frontier—a land of second chances and poseur aristocrats.

Now they just call it Trump country.

By twofold, Louisville, Kentucky, is the most populous city on the river. Bourbon country’s finest is followed by Pittsburgh, and then ever so closely by Cincinnati. Hunter S. Thompson, a native, declared Louisville “a Southern city, with Northern problems.” A Cincinnatian in the know told me his hometown is the inverse.

You see it when you’re there. Moving east and south across Ohio, Cincinnati is no Toledo. There is no quick-and-easy explanation of a glass industry gone away, no Detroit-style misery in miniature. Cincinnati is not comparable to Cleveland-Akron, Ohio’s Dallas-Fort Worth. Cincy has never suffered such a collapse in prestige. One hundred years ago, Cleveland was the fifth largest city in the United States—more fearsome than American-ancient Boston or nouveau Los Angeles.

Cincinnati is also not Columbus. First, Cincinnati is more likely to keep its name. (Roman generals are grandfathered in; explorers of the last six hundred years are not.) Second, unlike Columbus, Cincinnati is not anchored to a benign cult: the Ohio State University.

John Jeremiah Sullivan wrote that Ohio “has its very blandness and averageness, faintly comical, to cling to.” But these places are not so satirical. After all, there are hipster bars that could have been ripped from Hollywood (or anywhere these days). And there are early 20th-century homes (though often on German-named streets) refurbished by under-40s that could double as S.F. Victorians in a pinch.

More than anywhere else in the state, Ohio’s capital Columbus (and its more transient population) often seems intent on breaking its Midwest mold in such a fashion. Though such maneuvers all feel very self-aware—which is perhaps even more Midwestern.

Columbus is the fastest-growing city of significance in the state, though such materialist markers of success haven’t stopped many Ohioans from spouting complaints that could be heard in Northern Virginia, the Atlanta suburbs, and scores of towns across Texas, Florida, and anywhere in 21st century America that’s actually growing.

Last, and not least, and barely in the state, is Cincinnati and the overlooked Ohio River.

It still bears emphasizing: Eight presidents of the United States have hailed from Ohio. And seven were born in the state—including the seven that occupied the Oval Office from Reconstruction to the Roaring Twenties. Seven in half a century.

In contrast to the general understanding of American oligarchy, Ohio has been more important on the level of presidents than Harvard. Ohio politics in the Gilded Age was plausibly more important than the Democratic Party’s. And Ohio backrooms were nearly interchangeable with the GOP’s.

The last representative of this Ohio old guard was Senator Robert Taft, who in the early 1950s substituted “sane analysis for expediency” (his words), argued China not Russia was enemy number one, and exhorted Europe to be vaguely self-reliant.

Taft was defeated in his bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1952 by the most plausible heir to George Washington to date: Dwight Eisenhower. Taft’s ideas seemed, for a lifetime, to be settled business, as defeated as the druids.

Robert Taft’s father had been president of the United States and chief justice of the Supreme Court. Kids from even Southern Appalachia (a land of confusion and confused loyalty), like this writer’s grandfather, were named for the old man. For more than seventy years, to use a 21st century phrase, Robert Taft has been treated like the geopolitical version of a failson.

Even his father William Howard Taft, that stout figure who served between Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, was seemingly abandoned by history.

Yet along the Ohio River, up a road in Cincinnati named for the 27th president, there is a man some now think will be the 48th, and possibly the youngest ever.

In 10 years, Ohio has swapped places with Virginia on the political map. Now it is Ohio that is a soft red state a stone’s throw from Washington.

Sure, Akron is not Arlington-close, but there are portions of Virginia that are further west of Detroit. It’s not Arizona or Wyoming. And Ohio has the arsenal of would-be commanders-in-chief to match this new prestige that comes with being important, safe for the GOP, and an hour flight from power.

Before this shift, but after Taft, Ohio had a generation of usually Democratic grandees that seems strange and supine now.

There was Democratic Senator John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth and not the last to run a weird and blighted campaign for president. There was Republican Governor and before that Congressman John Kasich, reportedly brilliant and temperamental, but brilliant and temperamental about balanced budgets (fair) and Ukraine aid (much less so). It was a different time; it was certainly a different GOP.

There was Speaker John Boehner, beloved by the Washington press corps and the maître d’ at the Met Club. His tenure now is set to be lost in the noise of the Newt Gingrich revolution, the Dennis Hastert catastrophe, the Nancy Pelosi stints, the Paul Ryan story, and what could still be the GOP’s Year of Five Speakers.

There were more. Ted Strickland, Democratic governor in the Noughties and an ordained minister, was on Barack Obama’s vice-presidential search list when the Democratic Party felt the need to strike a middle ground in the culture war.

Notably absent from the Ohio national profile in these pre-Trump years was anything in the way of an effective punch on the issue of deindustrialization. It all went down, after all.

At the commanding heights, it was a process. As Charles Bukowski wrote in 1986: “Now in industry, there are vast layoffs (steel mills dead, technical changes in other factors of the work place). They are [laid] off by the hundreds of thousands and their faces are stunned: ‘I put in 35 years…’ ‘It ain’t right…’ ‘I don’t know what to do…’”

Especially after the collapse of communism, most statewide Republicans were tacitly for international laissez-faire. Both Democratic Senators at the time (including Glenn) and 11 of 19 congressmen voted against the North American Free Trade Agreement’s ignoble ratification. Among the Republicans voting in favor were Kasich and Rob Portman, the latter a Bushie U.S. Trade Representative and later U.S. senator.

In the meantime, many Democrats were content to rally support on these issues at the polls while often eliding immigration. They, too, seemingly achieved little.

By the late 1990s, dissent on these subjects was marginalized to such voices as James Traficant (the “oracle from Youngstown” to some, a convicted racketeer to others) and Dennis Kucinich (more on him a little later). In Britain, these figures would have been written off as “the loony left.”

This line of thought is certain to resurface this year as Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown seeks another term in office. He’s considered a state great, having been in elected office since the Seventies.

To his most cynical Republican critics, who have possibly been feeding lines to his opponent Bernie Moreno, Sherrod Brown is great like Elizabeth II was great. Like the late monarch, Brown is impossibly long in tenure and has been an overseer of precipitous decline.

For now, the old statewide consensus—what MAGA populists would now call “the uniparty”—is preserved in amber in the form of current Ohio Governor Mike DeWine. Presently, he is probably best described as an anti-anti-Trump Republican. Like the current president, DeWine’s been running for office since the ’70s. This is his last gig.

For the establishment, at least: après moi, le déluge.

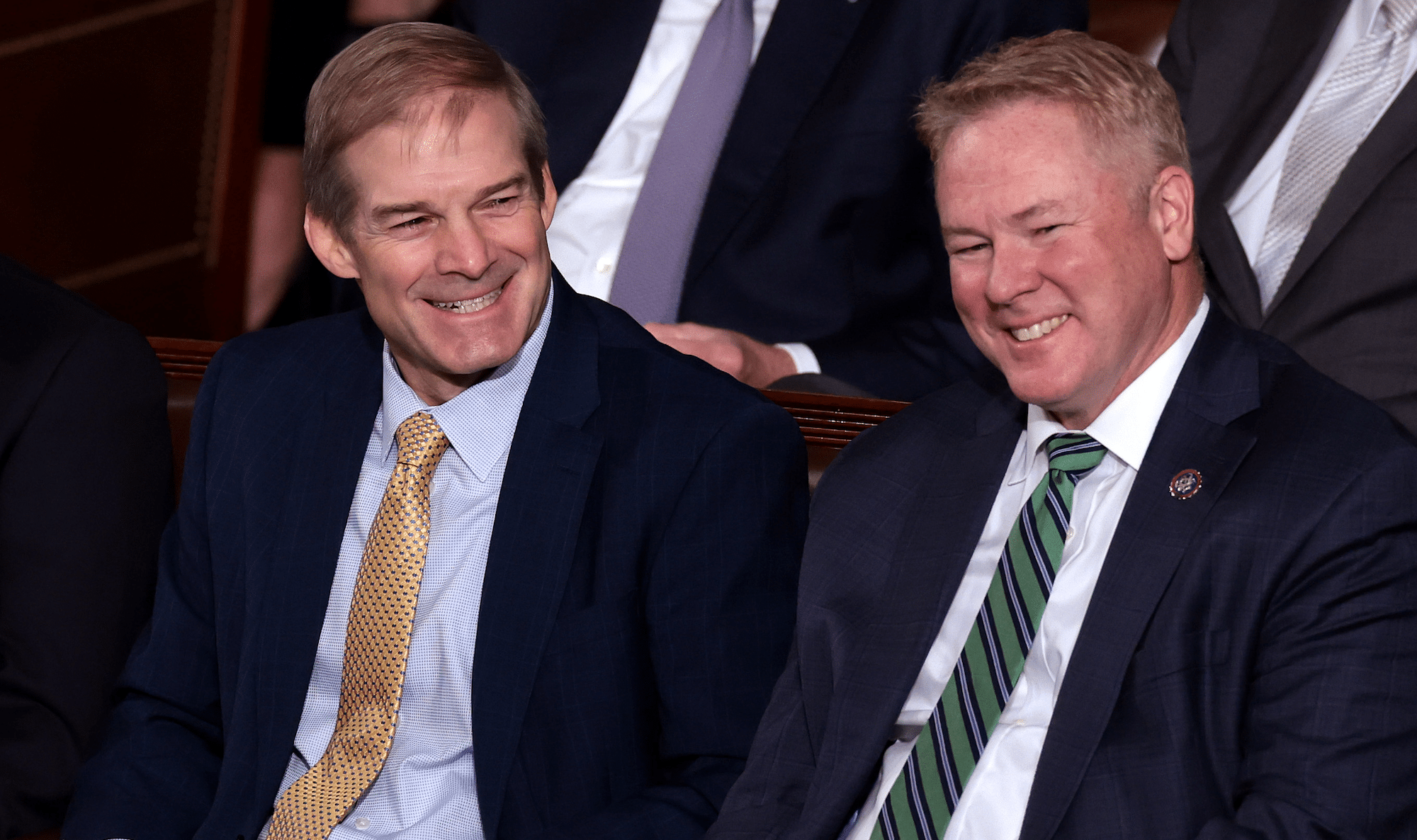

West of Columbus and Northeast of Dayton, there is Jim Jordan, the congressman who in many ways was first on board with the new tendency. An unremitting presence on cable news, in office since 2001, Jordan’s tradecraft has left him open to the critique that he is agnostic on governing.

In recent years, Jordan has sought—or been compelled by circumstance—to correct this impression.

The current chair of the influential House Judiciary Committee, Jordan attempted a bid for speaker in the mad scrum last autumn. If Speaker Mike Johnson’s tenure collapses before the November general election, Jordan may well be the odds-on favorite to succeed him.

Southwest in the Eighth District is below-the-radar player Warren Davidson. A West Pointer and former Army Ranger, the congressman’s “your word is your bond” personal style may be better suited for whatever comes after the Trump restoration—or the attempt at it that may soon end.

It is not unimaginable that Davidson could wind up a senior national security official under a President Trump next year. The former president has gone out of his way to show he means business this time, to the delight of both the right and the liberal press who have papers to sell.

On foreign policy, especially, the ex-president is short on allies and frankly running out of neocons he hasn’t fired. If a Senate vacancy opens up next year, Davidson could run for the upper chamber (he looked but passed on a run this year).

In the meantime, Davidson could take down a speaker of the House. Like a realist Georges Danton, no single member of Congress has communicated so proudly the imperative to end the old ways. That starts with bringing the war in the east to a close, or at least American sponsorship of it.

Dashing back to Columbus now is Cincy native and overnight Republican rock star Vivek Ramaswamy. The entrepreneur-turned-politician relocated back to Ohio in recent years. His wife is a physician at OSU. Ramaswamy passed on the 2022 Senate race only to dive headfirst into the 2024 presidential contest.

Ramaswamy has been compared derisively to Pete Buttigieg, another millennial Ivy League “gunner.” Past the mistiest similarities, it is an inaccurate comparison.

Buttigieg’s support was often bolstered by voters older than him. Ramaswamy, by contrast, seemed to rattle many establishment Baby Boomer conservative sensibilities while he built a youth fanbase online.

Buttigieg is taciturn. Ramaswamy is saber-rattling. Buttigieg is the bête noire of the Bernie Sanders wing. Ramaswamy is all in on Trump and Trumpism.

The Senate nominee this year, Moreno, is perhaps the biggest unknown.

A Hispanic-American and a career car dealer, Moreno’s background is plainly that of the kind of striver his party both seeks to attract and increasingly has come to represent. In his primary night victory speech, Moreno castigated the U.S. trade deficit with China.

Moreno has the staunch backing of much of the most populist and nationalist infrastructure in Washington, DC. But he does not have much in the way of an independent brand—it is one he will swiftly have to develop.

After all, a five-alarm fire, with way more than a whiff of the political dark arts, erupted at the eleventh hour in Moreno’s primary race. A 16-year-old alleged gay dating profile on an adult website. Was it Moreno’s?

“I reviewed all the available information and it showed that the account had only a single visit, no activity, no profile photo, consistent with a prank or someone just checking out the site. That’s it,” said AdultFriendFinder founder Andrew Cornu, denouncing the story. “It’s important to recognize that even temporary access to an email account is sufficient to create a fake dating profile in someone else’s name.”

For a party and a country seemingly debating abortion and gay rights this year with a fury not seen in decades, the impression of hypocrisy or even pathology could mean Senate control.

Even if one concedes the Republican talking point that Sherrod Brown is not all that he seems, the fact remains he has seemed just fine to voters. They have only once rejected him, in an Ohio secretary of state’s race over thirty years ago.

Coincidentally, Moreno is also the new father-in-law of Republican Congressman Max Miller. Both are from the Cleveland area. Miller, a 35-year-old freshman representative, is a Trump White House alum, a stalwart ally of Mar-A-Lago, but not generally associated with the party’s reformist wing.

Indeed, during the battle over Kevin McCarthy’s speakership, Miller broke with Florida Congressman Matt Gaetz, the anti-McCarthy ringleader, in furious terms. His critics see him as a grandiose foreign policy hawk. He said shortly after the October 7 Hamas atrocity that Israel should be bound by “no rules of engagement.”

Miller is running for reelection this year—against Kucinich (!), last seen running Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s presidential campaign. Kucinich left the RFK team in mid-October, as the candidate left the Democratic race to run as an independent.

Some near the Kennedy orbit have commented privately that Kucinich’s exodus lines up with RFK’s foreign policy post–October 7. Remarkably, on the Gaza war, Kennedy is arguably now the most hawkish of the three leading presidential candidates.

As Trump has urged Jerusalem to “finish up” and Biden has increasingly ceded ground to his progressive left, Kennedy has overtly rejected ceasefires and truces. This has won him plaudits from such arch-hawks as the Wall Street Journal editorial board and the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies.

“I don’t even know what that means right now,” Kennedy said in March of a potential stoppage in fighting. Each such cessation “has been used by Hamas to rearm, to rebuild and then launch another surprise attack. So what would be different this time?”

Surely these issues will soon come up on the campaign trail between Miller and Kucinich.

All these tensions, open disagreements and questions of authenticity and how they are settled—or not—will determine how much the Republican Party has really, truly changed.

No discussion of Ohio, of the Republican Party, or American politics is complete any longer without addressing Senator J.D. Vance.

For the subject at hand, he’s the 800-pound gorilla. Except what a poor analogy that is: the senator looks to be down about thirty pounds. The question of the hour is if he is, indeed, “central casting” to be Donald Trump’s second running mate.

At first, Vance might not make all that intuitive sense for the role. Shouldn’t Trump select a woman or a minority?

That is easier said than done, actually, as President Joe Biden found out in 2020. First Biden committed himself to the selection of a woman—it was a killing stroke to win the primary against Bernie Sanders in the waning normal days of 2020 (mid-March). By summer, the death of Minneapolis man George Floyd compelled Biden to select an African-American, ruling out white Minnesota politicians and former prosecutors such as Amy Klobuchar.

Trump has shrewdly not hemmed himself in so tightly, but another Biden-style precedent looms. Major party presidential nominees usually don’t select non-politicians or even backbench congressmen for a reason. Statewide politicians—elected senators and governors—are more heavily vetted, and are demonstrated survivors. Yet even selecting a governor of a less populous frontier state is fraught with risk, as John McCain learned with Sarah Palin.

Under this rubric, and ruling out clear apostates such as former U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley, the list is winnowed considerably: Vance; South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem; Florida Senator Marco Rubio; North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum.

With Rubio, the main problem is logistical. Both he and Trump are residents of the same state. Would Trump move his legal residence? Amidst a sprawling dragnet of criminal indictments related to his business and political practices? Would Rubio resign his Senate seat and move to another state for a race he might well lose?

Noem is bedeviled by a whisper campaign about marital infidelity. More significantly, Noem is in a double bind politically on social issues, cutting into her appeal as a feminine complement to Trump.

On the one hand, social conservatives view Noem as not hardline on the transsexual issue. In 2021, Noem declined to sign a transgender sports ban in college athletics, purposefully avoiding a fight with the NCAA. She cited her small state’s tourism concerns and her duty to her constituents. Conservatives such as Tucker Carlson disagreed, and the matter culminated in a Fox News showdown.

On the other hand, Noem signed into law an abortion ban that wiped away exceptions for rape and incest.

Noem gave a striking, inspired answer to Carlson a year later on the subject of Ukraine:

The primary external threat to the United States in Communist China. Our opposition to Russia has heightened this threat… The American people didn’t get us into this war. Joe Biden did. Biden has this fantasy that he can do the same kind of thing to Russia that Ronald Reagan did to the Soviet Union. … We’ve already overextended ourselves in our largesse to Ukraine.

But it’s likely, though not certain, that she’s staked out ground that has bled too many would-be allies.

Burgum is a dark horse in Vance’s way. It’s difficult to see what Burgum—Midwestern, tall, business experience, brains—brings that Vance doesn’t also while legitimately exciting people. Trump is said to fear anointing a successor. But picking the little-known if probably safe Burgum risks jumping the shark. Trump once also thought highly of Rex Tillerson.

The other question for Vance: Should he want the number 2 slot?

It is not a secret The American Conservative is a longtime confederate of the junior senator from Ohio. The upside is clear: No politician in America is as staked out as clearly on the stalwart issues of foreign policy realism, trade realism, and immigration restriction. No one. If Vance becomes vice president, he will be the runaway favorite to succeed a reelected Trump.

There is also the potential extraordinary circumstance that Trump wins but is forced from office by legal or financial issues or poor health (with a presumably corresponding set of pardons solving some of these issues). Vance, who turns forty in August, would become the youngest president in American history.

Yet, if Trump loses, or if he loses badly, not only does Trump go down but the most credible populist in the country is badly tarnished by a rout. Only one losing vice presidential nominee in over a century has later become president: Franklin Roosevelt. And it took FDR 12 years and the crisis of the Great Depression to recover politically from his loss on the 1920 ticket.

For Vance, then, this is a vabanque political moment less than two years into his Senate career.

It is especially so attached to a personality like Trump’s. The former president is the consummate gambler. Untold numbers of individuals have flamed out of his orbit.

Is this the move?

The personal fealty between Vance and the Trumps seems genuine. Vance is clearly tight with Trump’s eldest son Donald Trump Jr. Few have been able to strike the delicate balance between Trump’s personal affairs and Trump’s political prerogatives. Has Vance found it? It would be a major asset in office.

Much has been made of Vance’s highly bespoke political call in 2016: enthused and sympathetic about the issues Trump was raising, opposed to his becoming president.

Five years later, in autumn 2021, Vance (before he was a senator) told me Donald Trump would be reelected and inaugurated in January 2025. Back then, I ferociously disagreed. A major horseshoe political miss that Vance has recovered from could soon be capstoned by powerful prescience very few had.

It could make Vance the second most powerful person in the country.

Back when I started in journalism, I worked with the longtime columnist Michael Barone. In vivid contrast with most others I met, those who warned what a tough business media was, Barone reported the industry’s upsides. Barone had predicted Mitt Romney would win 315 electoral votes in the previous election with nary a professional consequence.

But Barone is hardly out to lunch, even if he joined organized conservatism’s strange sanguinity about the electoral appeal of Mitt Romney. He quickly followed up.

In his 2013 work Shaping Our Nation: How Surges of Migration Transformed America and Its Politics, Barone put forward the case (which would have huge relevance in 2016) that the Midwest is the most dovish region of the United States. The Midwest was notably settled by immigrants fleeing the wars of Europe. The Germans and even the Irish-Americans in the region were less likely to support any foreign policy perceived as too pro-British, which was increasingly a hallmark of U.S. foreign policy after the Civil War.

“Southernization” has defined U.S. demography and its politics for nearly a century and especially much of the last fifty years. Americans continued (and continue) moving south and west. Between 1976 to 2004, it became conventional wisdom that any Democratic ticket that had a prayer would have to feature a Southerner, probably at the top (Carter, Clinton).

From 1980 onwards, Republicans always featured a Southerner (and a Bush) except for 1996, an election in which the party was totally swarmed. The 1992 presidential race featured two Texas millionaires against the governor of neighboring Arkansas. The winning Democratic ticket of the 1990s was united by the Hernando de Soto Bridge in Memphis that links Tennessee and the Razorback State.

And then, all at once, the South disappeared from the big game.

In 2008, McCain-Palin vs. Obama-Biden skipped the region (unless you’re catching the current president on the occasional day he feels inclined to remind you that Delaware was a slave state). In 2012, Romney and Ryan were two Yankees. Parts of Indiana are arguably the South, but Mike Pence is not from that part.

And no Southerner is in the top tier of Trump vice presidential aspirants (Miami is not the South). Three Midwesterners (Vance, Noem, Burgum) are.

Given both the obscene housing crunch now hitting Florida and even Texas and the clear problems of the West Coast, the continued U.S. national move south and west may be no fait accompli. Much like Russia, the Midwest hopes to be a moonshot beneficiary of climate change.

Demographics could match political reality in the coming decade. For now, political reality is already here.

Midwest political influence—and Ohio Republican power, particularly—is back on the scene.

Originally found on American Conservative. Read More